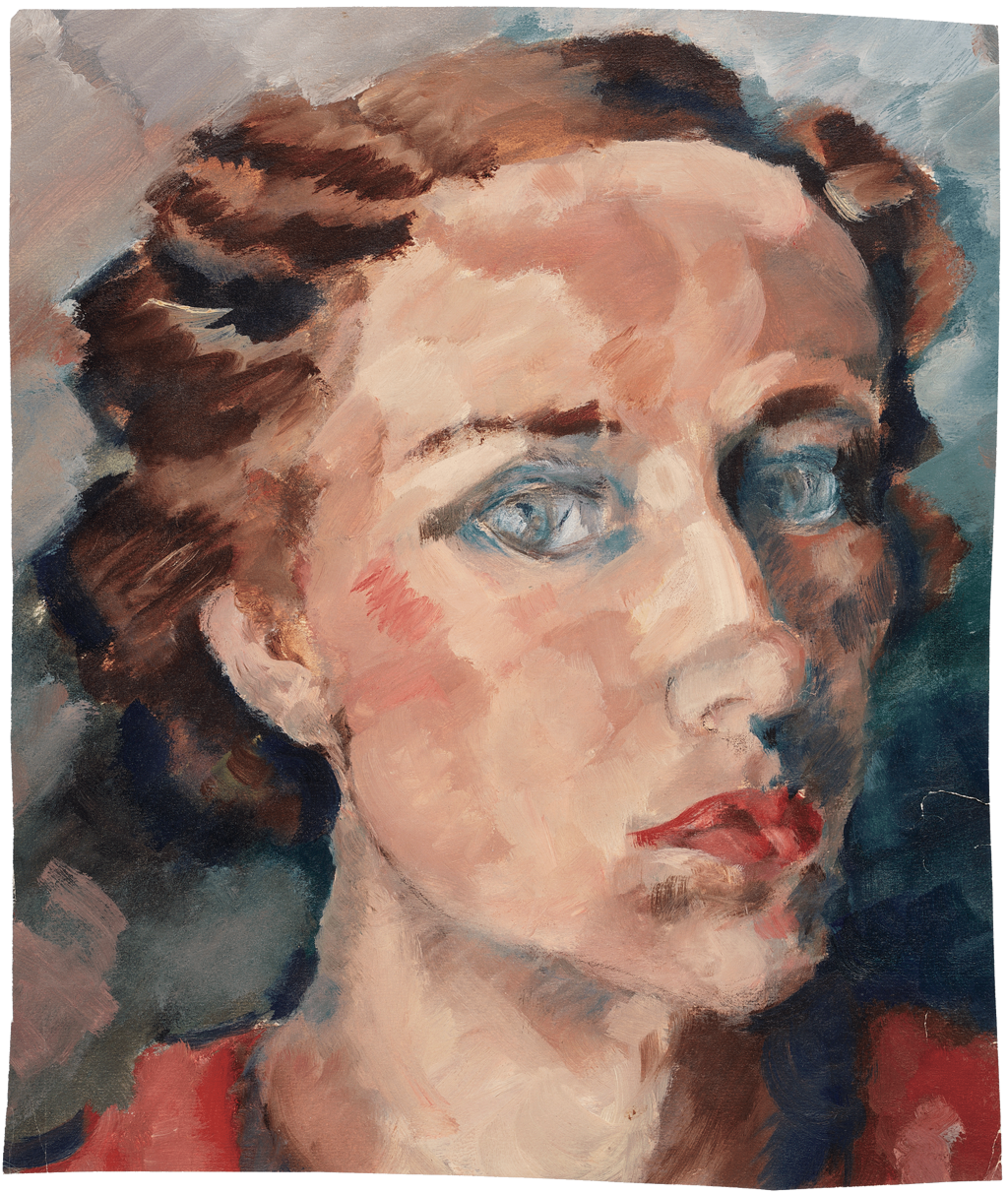

As early as 1945, the novelist denounced the misunderstanding on which the universal model is based. Since the dawn of time, it has been mistaken for the masculine gender, silencing women’s voices and making them invisible. When Jeanne Bornand, the housewife narrator and secretary in La Paix des Ruches, dares to write to let her voice be heard, as misplaced as that may be, it brings the gendered bias of our frame of reference to the fore. Alice Rivaz warned, “Beware of the woman who keeps silent. The day she speaks will change the world!”

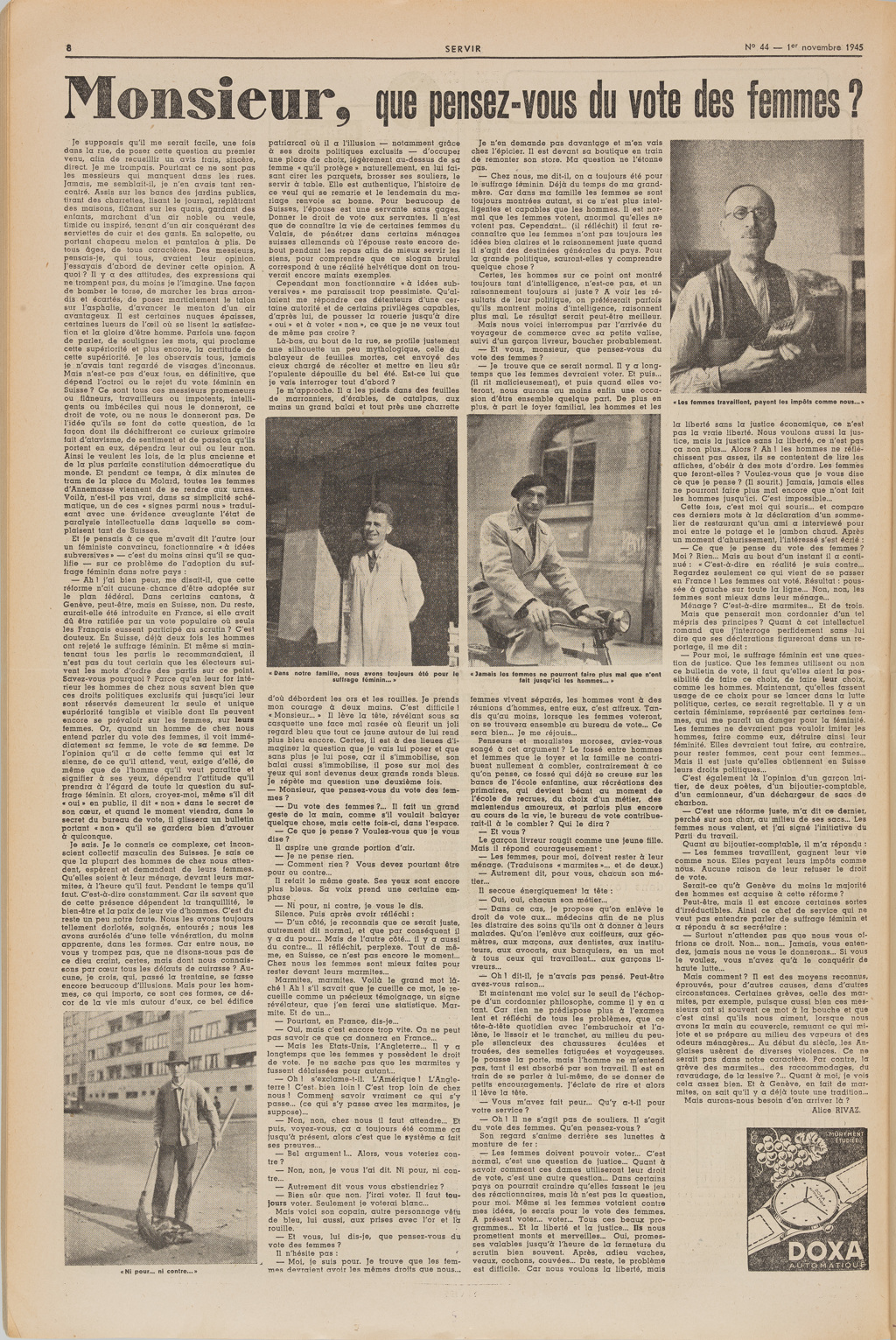

Although politically aware since her childhood, Alice Rivaz had to wait until the age of 70 before she could become a full-fledged citizen of her country. In November 1945, when Geneva issued a cantonal vote on women’s right to vote, she wrote this incisive article on the hypocritical resistance of men regarding women participating in politics.

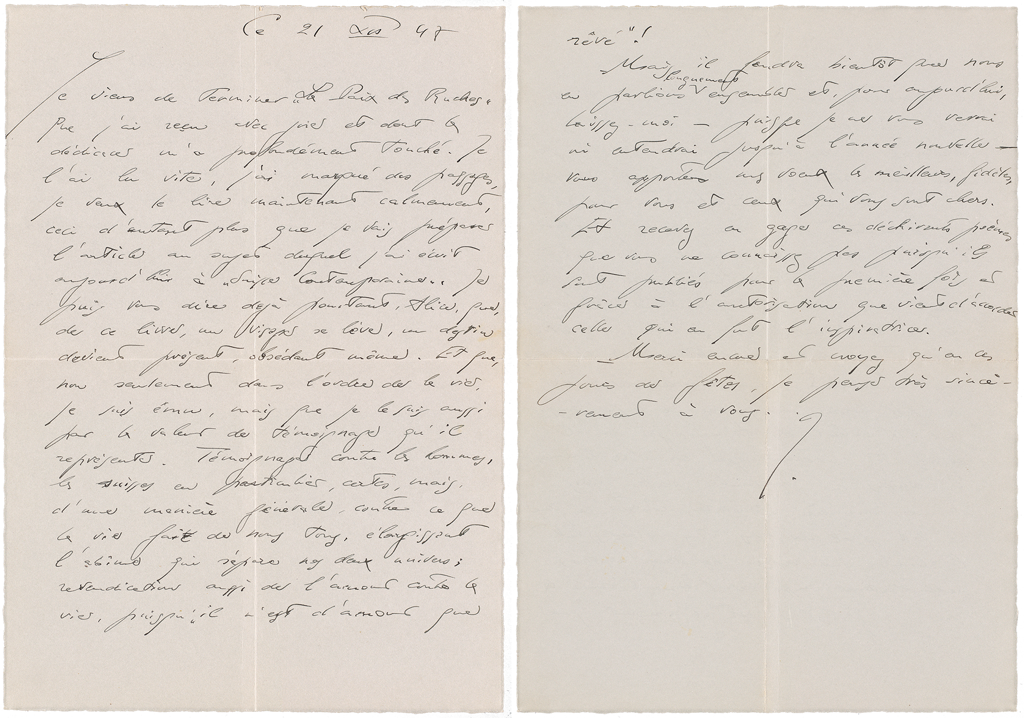

The poet Jean-Georges Lossier (1911-2004) was a loyal friend to Alice Rivaz. He actively contributed to the publication of La Paix des ruches and, during her long crossing of the desert between 1947 and 1959, he encouraged her to never give up writing, “your real job”.

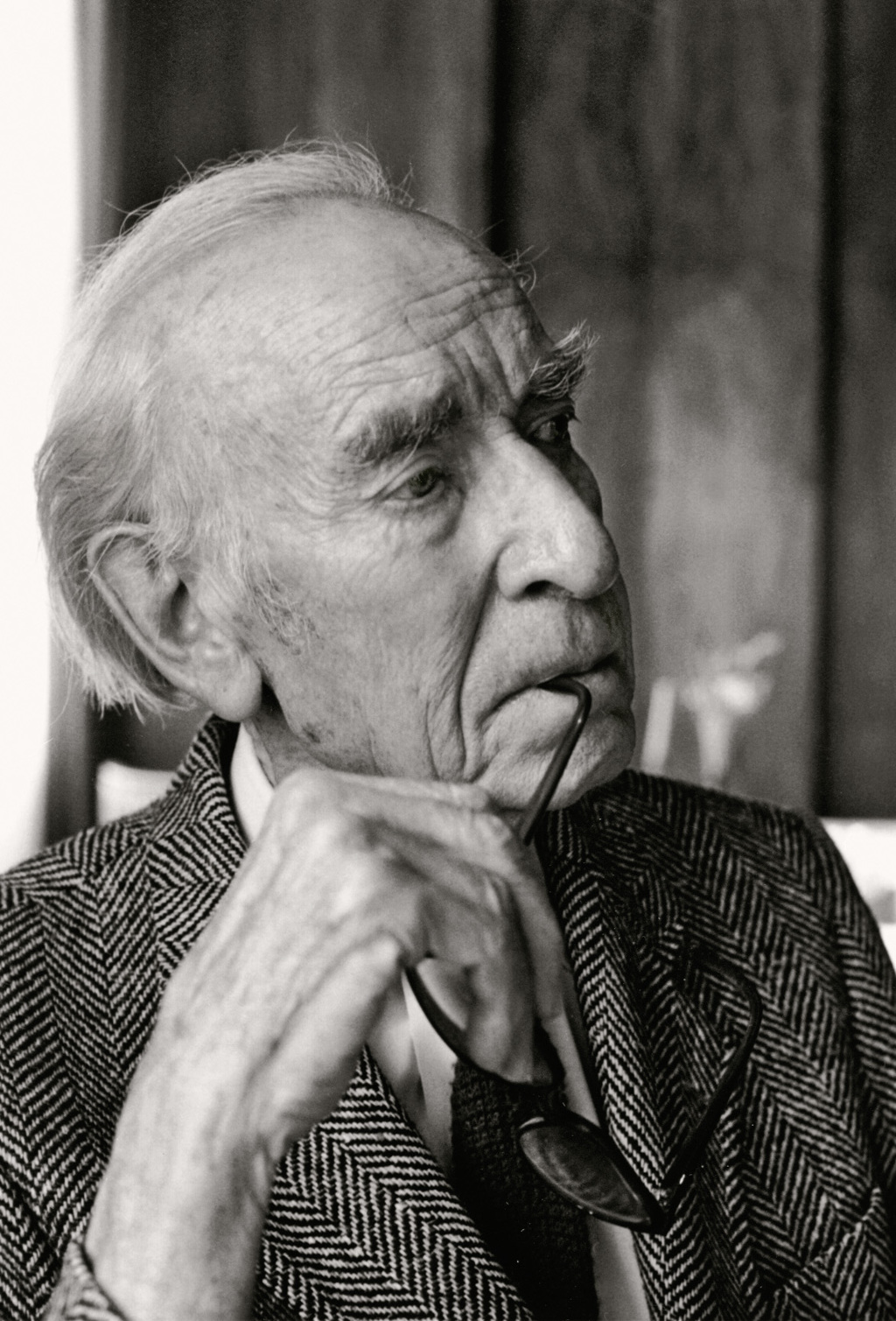

The reaction of the Vaudois author Paul Budry is representative of a caddish sense of male legitimacy, which often stifled the feminist debate in the 20th century. C.F. Ramuz did not understand La Paix des ruches any more than Albert Mermoud did. However, he admitted that he had never thought about the female condition while discovering the difference between ‘Mann’ (man) and ‘Mensch’ (human), which the French ‘homme’ conceals.

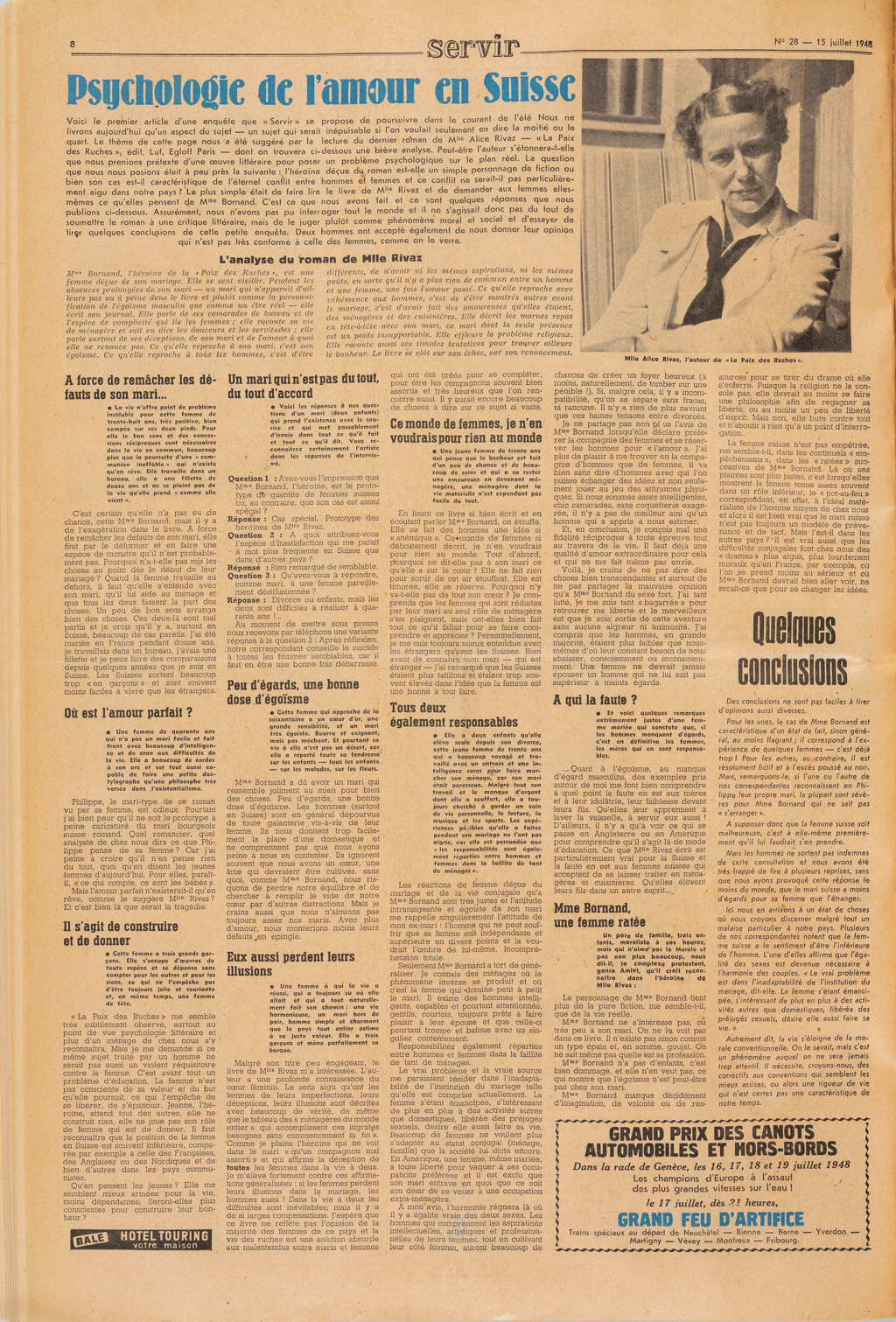

In 1948, the Servir newspaper used La Paix des ruches as the basis for an overview of the relationship between men and women in Switzerland. The reactions to the novel revealed a difference in interpretation based on gender. The empathy expressed by female readers suggested their longing to see society change, while the male readers simply pointed to Jeanne as solely responsible for her own dissatisfaction.

La Paix des ruches

La Paix des ruches (The peace within the beehive) was published two years before Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex and precedes the feminist novels of the latter half of the 20th century.

A new outlook

In creating new women’s voices in fiction, the novelist revives the memory of the female writers of the past.